Accident of PK 268, AP-BCP, A300 on 28 September 1992 on approach to Tribhuvan Airport Kathmandu

PIA Airbus A300 203B4, AP-BCP, the accident aircraft

Accident

- Date: 28 September 1992

- Summary: Controlled flight into terrain due to pilots’ error, improper navigation charts and failure of GPWS

- Site: Kathmandu, Nepal

- Aircraft type: Airbus A300B4-203

- Operator: Pakistan International Airlines

- Registration: AP-BCP

- Flight origin: Jinnah International Airport

- Destination: Tribhuvan International Airport

- Passengers: 155

- Crew: Captain Iftekhar Janjua; First Officer Hassan Akhtar, Supervisory Flight Engineer Ashraf, Operating Flight Engineer ? + 8 cabin crew

- Fatalities: 167 (all)

- Survivors: 0

From the official report: The ill-fated aircraft departed Karachi Airport Pakistan, at 0613 hours UTC on 28 September 1992 as Pakistan International Airlines Flight Number PK 268, a non-stop service to Kathmandu, Nepal. The accident occurred at 0845 UTC (1430 hours local time) when the aircraft struck a mountain during an instrument approach to Kathmandu’s Tribhuvan International Airport. The impact site was at an altitude of 7280 feet above sea level (2890 feet above airport level), 9.16 nautical miles from the VORDME* beacon and directly beneath the instrument approach track from the VORDME beacon (9.76 nm from and 2970 ft above the threshold of Runway 02 which is 77 feet below the airport datum).

The flight through Pakistani and Indian airspace appears to have proceeded normally. At 0825 hrs UTC (1410 hrs local time) two-way contact between Pakistan 268 and Kathmandu Area Control West was established on VHF radio and the aircraft was procedurally cleared towards Kathmandu in accordance with its flight plan. After obtaining the Kathmandu weather and airfield details, the aircraft was given traffic information and instructed to report overhead the SIM (Simara) non-directional beacon (214R VOR/39 nm from Kathmandu’s KTM VOR/DME) at or above FL150 (flight level on standard altimeter) as cleared by the Calcutta Area Control Centre.

At 08:37 hrs the copilot reported that the aircraft was approaching the SIM beacon at FL 150, whereupon procedural clearance was given to continue to position SIERRA (202°R/10 nm from the KTM beacon) and to descend to 11,500 feet altitude. No approach delay was forecast by the area controller and the co-pilot correctly read back both the clearance and the instruction to report at 25 DME. At 08:40:14 hrs, he reported that the aircraft was approaching 25 DME whereupon the crew were instructed to maintain 11,500 feet and change frequency to Kathmandu Tower. Two-way radio contact with the Tower was established a few seconds later and the crew reported that they were in the process of intercepting the final approach track of 022M (Magnetic) of Radial 202 KTM VOR ) They were instructed to expect a Sierra approach and to report at 16 DME. At 08:42:51 hrs the first officer reported “One six due at eleven thousand five hundred”. The tower controller responded by clearing the aircraft for the Sierra approach and instructing the crew to report at 10 DME. At 08:44:27 the first officer reported 10 DME and three seconds later he was asked, “Report your level”. He replied, “We crossed out of eight thousand five hun,’ two hundred now”. The controller replied with the instruction “Roger clear for final. Report four DME Runway zero two”.

The copilot responded to this instruction in a normal, calm and unhurried tone of voice; his reply was the last transmission heard from the aircraft, thirty-two seconds after the copilot reported 10 DME the aircraft crashed into steep, cloud-covered mountainside at 7,280 feet amsl and 9.16 nm on radial 202 of KTM VOR

Personnel information

Aircrew

| Commander | Pakistani male aged 49 years | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Licence | ALTP # 373 issued by Pakistan CAA on 3 Nov 73 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Certificate of Validity | Valid to 9 Dec 92 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Types on licence | Group 1: Airbus A-300 Group 2: None | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Instrument Rating | Renewed 21 May 92 valid to 9 Dec 92 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Instructor Rating | Route check pilot wef 12 July 87; Simulator instructor wef 8 Jun 89 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last route check | 25 May 87 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last simulator check | 2 1 May 92 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last medical check | Class 1 medical renewed on 31 May 92 endorsed “subject to use of corrective glasses”. The commander’s hearing acuity had been reducing over a period of years and at his last audiometry check, on 19 November 1990, it had reduced to the category of “borderline”. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hours flown (at time of reporting for duty on 28 Sept 1992) | Type A300: command 6260:30, copilot 1.00; Type B707/720: command 2136:46, copilot 726:23; Type DC-10: Copilot 888:30; Type Propeller aircraft: command 1493:35, copilot 1688:18 | Total command 9890:51; Total copilot 3295:44; Grand Total 13186:35 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recency (flight hours at time reporting for duty on 28 September) | Previous/hours/mins | 24 hours = 0; Month = 36:13; 3 months = 121:41; 6 months = 223:38; Year 605:31 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duty period last 24 hours | 3 hrs 45 mins | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Previous operations to Kathmandu during 1992 | 23 July; 20 February; 6 February; 9 January. |

| Copilot | Pakistani male aged 38 years | |||||||||||||||

| Licence | CPL # 842 issued by Pakistan CAA on 24 Dec 1984 | |||||||||||||||

| Certificate of Validity | Valid to 11 Nov 92 | |||||||||||||||

| Types on Licence | Group 1 : None Group 2: Airbus A-300 | |||||||||||||||

| Instrument Rating | Renewed 23 Jun 92 valid to 28 Dec 92 | |||||||||||||||

| Instructor Rating | None | |||||||||||||||

| Last Route check | 10 April 91 | |||||||||||||||

| Last simulator check | 23 Jun 92 | |||||||||||||||

| Last medical check | Unrestricted class 1 medical renewed on 21 April 1992 | |||||||||||||||

| Hours Flown (at time of reporting for duty on 28 September) | Type A300: copilot 1469:26; ; Type B737: copilot 518:48;Type Propeller aircraft: command 295:20, copilot 3565: 26; | Total command 295:20,; Total copilot 5553:40;;Grand Total 5849:00 | ||||||||||||||

| Recency (flight hours at time reporting for duty on 28 September) | Previous/hours/mins | 24 hours = 3:57; Month = 67:43; 3 months = 196:45; 6 months = 378:32; Year 625:08 | ||||||||||||||

| Duty rest period last 24 hrs | 3 hrs 45 mins | |||||||||||||||

| Previous operations to Kathmandu during 1992 | 18 June 1992 |

| Operating Flight Engineer | Pakistani male aged 40 years | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Licence | FEL # 224 issued by Pakistan CAA on 13 March 82 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Certificate of Validity | Valid to 24 Nov 1992 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Types on licence | Airbus A-300 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Instructor rating | None | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last route check | N/A (Recently returned from 3-year secondment to Malaysian airlines and operating under supervision) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last simulator check | 18 Sept. 1992 (by Malaysian airlines) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last medical check | Unrestricted class 2 medical issued on 11 Dec 91 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hours flown (at time of reporting for duty on 29 Sept) | Type A300 2516:25; Type B707/720 2773:26 | Total 5289:51 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recency (flight hours at time reporting for duty on 28 September) | Previous/hours/mins | 24 hours = 3:57; Month = 24; 3 months = 3:24*; 6 months = 3*: 24; Year | *Had flown 1634.08 hours during secondment to Malaysia between Aug 1989 and 18 Sep 1992 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duty Period last 24 hours | 3 hrs 45 mins | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Previous operations to Kathmandu during 1992 | None |

| Supervisory Flight Engineer | Pakistani male aged 42 years | |||||||||||||||

| Licence | FEL No 185 issued by Pakistan CAA on 25 Sep 1978 | |||||||||||||||

| Certificate of Validity | Valid to 10 December 1992 | |||||||||||||||

| Types on licence | Airbus A-300 | |||||||||||||||

| Instructor rating | Route check engineer wef I5 Nov 88; Simulator instructor wef 20 Feb 89 | |||||||||||||||

| Last route check | Last route check: 29 May 92 | |||||||||||||||

| Last simulator check | 10 Sep 1992 | |||||||||||||||

| Last medical check | Class 2 Medical re-issued on 25 May 92; Medical category withdrawn on 13 April 1992 for 4 weeks due to a diabetic problem | |||||||||||||||

| Hours flown (at time of reporting for duty on 28 Sept) | A300 4503:53; B707/720 3716:56 | Total 8220:49 | ||||||||||||||

| Recency (flight hours at time reporting for duty on 28 September) | Previous/hours/mins | 24 hours = 1:00; Month = 46; 32; 3 months = 161:37; 6 months = 185; Year 492 | ||||||||||||||

| Duty Period last 24 hours | 3 hrs 45 mins | |||||||||||||||

| Previous operations to Kathmandu during 1992 | Before 1 April 1992 |

Air Traffic Control

There were several controllers on duty in Air Traffic Control at the time of the accident but only the Tower controller was in R/T contact with the aircraft during its approach; Tower controller: Nepalese male aged 35 years; Licence: not issued and not required under Nepalese regulations; Ratings: not formally issued. All controllers are trained for and rotate through the Area Control Centre, Air Traffic Services (ATS) reporting office and control tower positions after qualifying as controllers; Training: completed 52-week ATC course in Kathmandu in February 1982. Completed approach control (non-radar) course in Sri Lanka in December 1991; Experience: employed as an air traffic controller at various Nepalese airfields since completion of Nepalese training in February 1982. Returned to Kathmandu airport in early1990; Duty period last 24 hours: 3 hrs 30 mins

Extract of Evidence

The aircraft struck ground 7,280 feet above sea level on the correct final approach track at 9.16 DME. At that DME the aircraft would normally have been descending through 9,000 feet although the minimum safe altitude was 8,200 feet. At impact the slats, flaps, spoilers and landing gear were correctly configured for landing. The aircraft’s wings were level, its heading was consistent with maintaining track and the airspeed was about 14 knots above the final approach speed. Both engines were at flight-idle for most of the descent but were producing slightly more than idle power at impact. The pitch (fuselage) attitude was near zero (level) which, for the configuration and power setting, was consistent with the rate of descent required to follow the altitude profile shown on the approach chart. Then was no evidence of pre-impact fire, explosion, disintegration or major mechanical malfunction.

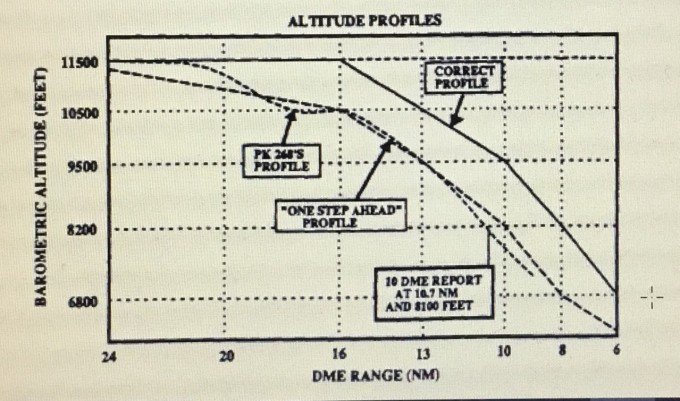

The copilot reported WE CROSSED OUT OF EIGHT THOUSAND FIVE HUN TWO HUNDRED NOW five seconds after starting his 10 DME position report However, the crew made their 10 DME report at 10.7 nautical miles from the beacon when the aircraft was passing through 8,100 feet. If, for whatever reason, they thought they were at 10 DME, then they were close to their target altitude of 8200 feet The initial reference to “FIVE HUN which was rapidly amended to “TWO HUNDRED’ may have been because the previous target altitude was 9,500 feet; certainly, the aircraft was closer to 8,200 than 8500 feet when the transmission started.

On this misinterpreted profile, they should have expected to be midway between 8,200 feet and 6,800 feet halfway between the check ranges of 10 and 8 DME. This would place them at 7,500 feet at their estimate or indication of 9 DME. At the groundspeed of 168 kts, the time to cover one nautical mile is 21 Seconds. The 10 DME call started 32 secs before impact so, if the DME range error was consistent, they would see 9 DME 21 seconds after the R/T call and 11 seconds before impact.

Therefore, if they were attempting to regain the ‘one step ahead’ profile they should have been less than 100 feet below 7,500 feet 11 secs before impact. An FDR “snapshot” 12 seconds before impact showed the aircraft at 7,484 feet which means they were just 56 feet below their target (one step ahead) profile and correcting towards it.

There is a very close match between the altitudes achieved by PK 268 and the target altitudes obtained by misreading the altitude profile through being ‘one step ahead’. The match is almost perfect if the crew’s position report at 10 DME is accepted as meaning the crew believed they were at precisely 10 DME. Proof that the crew had mis-interpreted the chart by ‘one step ahead’ would be some indication that they were attempting to match 9500 feet to 13 DME, 8,200 feet to 10 DME. and 6800 feet to 8 DME.

Forecast weather

Terminal aerodrome forecasts (TAFs) were issued by the Kathmandu meteorological office at 0100 hrs UTC and again at 0300 hrs UTC. For the time of the accident, there was no significant difference between the forecasts which were: Wind 240°/08 kts, visibility more than 10 kilometres, 2, later, 3 oktas of stratocumulus (SC) base 3000 feet aal (above airfield elevation), 3 octas of altocumulus (AC) base 10,000 feet aal and temporarily 1 octa of cumulonimbus (CB) base 2000 feet aal.

Observed weather

Routine weather reports for Kathmandu airport are issued at 50 minutes past the hour. The report preceding the accident and the report issued five minutes afterwards are tabled below

Pilot reports

The commander of an aircraft which arrived at Kathmandu two hours before the accident reported that there was a large cumulus cloud developing into a cumulonimbus to the east of the Sierra approach track at 28 DME and a well-developed cumulo-nimbus cloud on the approach track at about 18 DME. He diverted by some 5 to 7 nautical miles off-track to avoid the second cloud, remaining in VMC (visual meteorological conditions), and then regained track. He did not see the airport until 8 DME. He also stated that, in his experience, at that time of the year any turbulence encountered is invariably associated with cloud.

The commander of the aircraft which completed the preceding Sierra approach, one hour before PK 268, stated that he experienced no turbulence between 25 DME and landing. There was an easterly wind of about 10 knots during the approach and one or two cumulo-nimbus clouds two or three nautical miles east of the approach path. From 16 DME to 5 DME he was in IMC (instrument meteorological conditions) within cumulus cloud and rain was encountered between 8 DME and 5 DME. He broke out of cloud at 6000 feet above sea level (asl (1700 ft above airport level (aal) and the runway was visible from that time.

The commander of Pakistan 268 reported to the Calcutta and Kathmandu area control centres that in the vicinity of the Nepal/Indian border, he was deviating by 10 to 15 nautical miles to the right of planned track to avoid towering clouds. About 55 nautical miles from Kathmandu he broadcast a message to his passengers on the Cabin PA (passenger address) system stating that “The weather built up very fast in the area of such nature over the Himalayan Range”; he then relayed to them the Kathmandu weather report in general terms. At 0838:41 (about 34 DME) whilst in descent from FL 150 to 11,500 feet, he made another PA broadcast to the passengers and cabin crew stating, “We are entering into the area of turbulence and I request all of you to remain seated”.

Weather at the accident site

Eye witnesses close to the accident site at the time of impact stated that there was little or no wind, no rain and no thunderstorm in their vicinity. The visibility was about 20 metres in mist. Observers at the airport reported that small patches of blue sky was visible but the tops of the mountains to the south of the airport were hidden by cloud.

Aerodrome

Tribhuvan International Airport is situated in a bowl-shaped valley about 14 nautical miles in diameter and surrounded on all sides by high ground. The minimum safe altitude to the north of the airport is 21,000 feet; to the south it is 11.500 feet. The transition altitude is 13,500 feet. The aerodrome reference point is at N 27,41.8′ E 85, 2.17

The airport elevation is 4390 feet above mean sea level. There is a single bitumen runway aligned 022°/2020 which is 3050 metres long (10065 feet) and 46 metres wide (151 feet). The Runway 02 threshold elevation is 4313 feet. All relevant airport facilities were reported as serviceable.

Air Traffic Control Procedures

The Kathmandu FIR (Flight Information Region) is divided into two sectors: Nepalgunj to the West and Kathmandu to the East of longitude 83 degrees East. The Kathmandu sector is further divided into two sub-sectors: East and West. The division is aligned with the 160 degree and 360 degree radials from the VOR beacon. The aerodrome control zone (CTZ) extends from ground level to 8500 feet amsl out to 10 nm. The TCA (terminal control area) extends out to 25 nautical miles from the aerodrome from 8500 feet to FL 460. The area to the north of the aerodrome is shaped, due to the main, and is defined in the Nepalese ADJ.

There is no radar at Kathmandu. Control of IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) traffic is procedural and based on position reports relative to the VOR/DME beacon. Control of all traffic in the control zone and traffic in the TMA at and below 11,500 feet is vested with the Tower controller.

Instrument approach procedures

There are two published instrument approach procedures to the airport The Echo approach from the east and the Sierra approach from the south. Airways traffic arriving from the Calcutta FIR normally arrives using the Sierra approach procedure which has been in use since 1978. It is published on charts available from at least four sources (HMG/N Dept of Civil Aviation; Jeppesen, SAS and Aerad). A copy of the Jeppesen Sierra approach chart which should have been used by the crew of PK 268 is at Appendix B. However, there was evidence to suggest that many crews made a hand drawn version of the procedure, in order to clarify the letdown, and used this rather than the official chart during the procedure.

Accident site details

The aircraft crashed into the southern flank of a mountain 9.76 nautical miles from the threshold of Runway 02. The impact point was assessed as 7,280 feet above sea level which was some 150 ft below the crest of the mountain. The average slope of the impact area was 45 degrees with some areas, including the cockpit impact point, being close to the vertical. The was a steep gulley below the main impact area, into which many items of wreckage had fallen. The aircraft was almost totally destroyed by the impact and subsequent fire

PIA Training Policy

The training policy section of PIA’s Fight Operations Manual dated 29 May 1988 and approved by the Pakistan Civil Aviation Authority (CAAP) did not state the 288 ICAO Circular 296-AN1170 requirements for renewal of pilot’s supervisory ratings. These requirements were, however, contained in the earlier training policy document dated 18 May 1982. This policy document stated:

- Flight/Simulator Instructors will be exempted from Command Renewal Checks/Route Checks. However, they will have to do their Instrument Renewal checks.

- A Route check Pilot is exempted from route checks but must fulfil the other formalities for his licence renewal.

Flight Crew Qualification for Kathmandu

PIA’s training policy document of May ’88 listed route qualification requirements for pilots but not flight engineers. Route/airfield qualifications were combined and based on the concept of area qualifications. Qualification requirements were divided into aircraft categories and then subdivided by geographic area and airfield. There were four methods of qualification (quoted verbatim):

- In flight familiarisation as a member of the flight as an observer.

- Familiarisation by means of programmed instructions on route documentation. (RCU)

- Simulated means used to acquaint pilot in the use of the instrument approach to land, arrival and departure procedures which he may utilise in the operation. (These sessions would also include route and area briefing).

- Route checks to demonstrate adequate knowledge of route/airfield

Qualification was valid for one year. Pilots were expected to know (amongst many other details) the terrain and minimum safe altitude for an airport.

The appropriate area for Kathmandu was India/Bangladesh. Within this area Kathmandu was listed as not requiring qualification for captains and copilots of wide-bodied aircraft such as the A300 but it was required for Boeing 707/737 pilots.

Crew training records

The crew’s training records were scrutinised for any unusual entries which might have been relevant to this accident There were no such entries in any file except the commander’s. The relevant entry in his file related to his landing at Kathmandu on 5 October 1989 when he braked so heavily that the main wheel tyres of his aircraft deflated after landing. The episode came to the attention of the Chief Pilot A300 who wrote the following letter to the commander:

“While operating PK-264/051089, during approach Flight Recorder read out shows excessive rate of descent and speed which resulted in activation of fusible plug deflating tyres after landing. A circular issued in June 1989 and T-chart gives definite procedure to be followed for this airfield which was not adhered to. Director of Flight Operations is displeased on this incident and you are hereby cautioned to be more careful in future.”

PIA Services to Kathmandu

PIA had approximately 44, A300 flight crews and only two scheduled flights to Kathmandu per week on Mondays and Thursdays. The Monday flight was usually flown by a Boeing 707 and the Thursday flight by an A300. However, on Monday 28 September, the traffic load was such that it required an A300.

Flight Simulator

Tests were carried out in an A300-B4 flight simulator in the presence of representatives from Airbus Industries and the investigation team. The following parameters relating to the accident flight were simulated: motion; weight; centre of gravity; atmospheric conditions; airport altitude and VOR/DME position. The terrain surrounding Kathmandu was not simulated.

The objectives of the tests were:

- To examine aspects of the flight deck ergonomics.

- To examine the aircraft’s autopilot/autothrottle relationship.

- To examine the relationship between indicated airspeed and rate of descent in the landing configuration

- To reproduce the last I5 miles of the accident flight

- To fly the correct SIERRA approach flight profile

- To examine modified SIERRA approach procedures

- To examine procedures for terrain avoidance following an unexpected ground proximity warning.

- To record the tailplane aim position (TPI) during the approach.

The tests showed that

- Approach charts were difficult to read if they were placed under the clip between the inertial navigators on the control pedestal, because the eye to chart distance was 92 cm at an angle of about 40′ from ahead. Moreover, the speedbrake selector handle, whether in the stowed or the armed position, obscured the commander’s view of the lower half of the chart. If placed under the clip on the side wall, the eye to chart distance was 48 cm and charts were readable if the pilots turned their heads through about 40°and looked even further to the side. Charts were easily read if they were placed under the clips on the control columns, where the eye to chart distance was about 40 cm and the chart was directly in front of the pilot.

- The volume of the flight deck loudspeakers was reduced during radio transmissions made by the pilots using hand microphones.

- The GPWS audio warning was emitted through both flight deck speakers; the warning volume could not be adjusted by the pilots and it was unaffected by simultaneous radio transmission.

- The approach profile flown by PK 268 could be replicated without using speedbrakes or unusual manoeuvres. The profile simulated by following the airspeeds, altitudes and configurations used by the crew of PK 268 resulted in a very similar flight profile to that recorded by the FDR

- In the landing configuration, with engine thrust at idle and airspeed at Vapp, the rate of descent was about 1,600 feet per minute. On a SIERRA approach the aircraft was always significantly above the minimum altitudes at 8, 6, 5 and 4 DME. If the rate of descent was maintained after 4 DME the aircraft intercepted a 3-degree slope between 2 and 3 miles from the runway threshold. These characteristics were very similar to those predicted by PIA’s senior A300 check-pilot

- At Vapp + 15 k nots, the rate of descent increased to 2,000 feet per minute and was sufficient to match the SIERRA minimum altitude descent profile between 10 DME and 4 DME. The aircraft could be descended to the minimum altitudes for 8.6 and 5 DME, although the autopilot workload was much increased above that required to fly the approach at Vapp.

- With 6,800 feet set on the autopilot altitude selector, in the same conditions as sub-para ‘f’ above, the autopilot began to reduce the pitch attitude between 7,600 and 7,400 feet. In a repeat of the test with 151 knots set on the autothrottle speed selector the engine thrust increased to maintain airspeed as the nose rose. The pitch attitude and thrust lever activity at 7200 feet was very similar to that recorded on the FDR during the three seconds before impact.

- Modifying the SIERRA approach profile to have one 6 degrees approach slope (instead of four) between 10 DME and 4 DME made the approach more stable and easier to fly because fewer and smaller changes to pitch attitude were required to maintain the optimum descent profile. This profile was flown at Vapp + 10 to 15 knots.

- If the “go-around” button on a thrust lever was depressed during a simulated approach in the landing configuration, with autopilot engaged and engine thrust at idle, the aircraft descended a further 120 feet and regained the altitude at which the button was pressed within 12 seconds. The ensuing climb with gear retracted and flaps at 15 degrees stabilised at a pitch attitude of 15 degrees and a climb rate of 2400 feet per minute, Pilot intervention did not succeed in reducing the amount of height lost and the time to regain the original height was reduced by just one second.

- The tailplane trim setting, at 9 DME on each approach made in the landing configuration was between 6.5 degrees and 7. 5 degrees. depending upon instantaneous speed and angle of descent.

GPWS (Ground Proximity Warning System)

It is unfortunate that a timely GPWS warning depends so heavily on the distance between the aircraft and the ground beneath it rather than the ground ahead of it, a dependence which has obvious limitations in mountainous terrain. The system cannot be optimised for every type of terrain and the majority of international airports are surrounded by lower and less steep terrain. In these areas, the equipment has worked well and has prevented accidents. To have prevented this accident, the equipment would have had to warn the crew at least 15 and, allowing for typical pilot reaction times, probably 20 seconds before impact. At that time the aircraft was almost a mile away from the mountain it hit and over 500 feet above the ground directly beneath it

GPWS Improvements

Thc GPWS system could be augmented by giving it a capability to look forward as well as downwards. Two methods of achieving this would be forward looking sensors and digital map compilation correlation (a navigation system which computes position by comparing the terrain profile sensed by the radio altimeter or laser to terrain elevation data stored in a digital computer navigation). Both are existing military technologies and there may be scope for adapting these technologies for civil aviation. A detailed analysis of the systems is beyond the scope of this report Nevertheless, it is recommended that ICAO should sponsor research into improving GPWS technology so as to improve system performance in mountainous terrain.

Crew reaction to GPWS

There were no written procedures for pilots to follow in response to a GPWS warning except for one paragraph in the aircraft manufacturer’s operating manual under the FINAL (approach) section of the normal procedures which was repeated in PIA’s A300 SOPS. The stated procedure was:

“in case the GPWS is activated react with pitch control and power without delay”

This statement is common sense but not as useful as it might be, In visual conditions the pilot can judge the appropriate reaction himself but in cloud it begs the questions: how much pitch and how much power? The procedure for swiftly establishing the maximum sustainable climb angle is what the pilot really needs to know. Therefore, it is recommended that Airbus Industries should amplify the instructions in their Flight Crew Operating Manual regarding pilot response to GPWS warnings.

Operation: A GPWS was fitted to the aircraft to prevent inadvertent controlled fight into terrain. The equipment has five different sets of conditions known as modes which trigger aural and visual warnings on the flight deck. The aural warning is a synthetic male voice broadcast by the flight deck loudspeakers irrespective of whether or not the crew were using headsets. The visual warnings include a red light labelled “PULL UP” on each pilot’s instrument panel. Of the five modes, only modes 1 and 2 are intended to warn the crew of and abnormally high rate of descent depending on ground proximity. These were:

- Mode 1: Excessive (barometric) rate of descent relative to the terrain.

- Mode 2: Excessive terrain closure rate (the rate at which radio height was reducing)

Modes 1 and 2 have maximum and minimum radio heights above and below which all “SINK RATE”, “TERRAIN” and “PULL UP” warnings are suppressed.

Between these heights, the conditions which trigger a warning vary as a function of several parameters including Mach number (a derivative of true airspeed), radio altitude, barometric sink rate, terrain closure rate and flap position. Also, in the landing configuration, the mode 2 warning is cut off between 200- and 600-feet radio height as a function of barometric descent rate to minimise nuisance warnings during approaches.

The system may be tested by the crew before flight. The built-in-test produces a “PULL UP” audio warning and illuminates lights on the instrument panel. System failure during test is indicated by the absence of a warning and or the illumination of a GPWS FAIL’ lamp on the control panel.

Radio Altimeter

The aircraft was fitted with two independent radio altimeters which indicated height above the ground up to a maximum of 2,500 feet via indicators on each pilot’s instrument panel. A movable decision height index could be set by the pilots up to a maximum of 499 feet Amber lights and an audio warning would be triggered when the aircraft descended through the decision height set on the indicators. One radio altimeter recovered from the accident site had the decision height index set to 499 ft

The radio altimeter was unlikely to have alerted the crew since the decision height on at least one of the indicators was set to 499 feet, the maximum setting. The more modern GPWS computers generate a synthetic voice warning of “MINIMUMS! MINIMUMS!” when the aircraft descends to the decision height set on the radio altimeter. The minimum descent height for the SIERRA approach is 807 feet. If the crew of PK 268 had had the ‘smart’ radio altitude callout of ‘minimums’ (they did not), and if they had been able to set 807 fat as a decision height (they could not, 499 was the maximum), then they would have heard a ‘minimums’ warning some 25 seconds before impact. This warning could have alerted the crew to the fact that they were below the required approach profile and possibly enabled them to take timely remedial actions to avoid ground impact. Enabling the ‘minimums’ smart callout is a minor modification which requires wiring from the radio altimeter to the GPWS.

The Marks V to VI1 GPWS also have ‘smart’ radio altitude callouts only heard on non-precision approaches. In view of the superior technology available, it is recommended that all airlines which operate regular scheduled services to Kathmandu should, where necessary, modify their GPWS equipment to provide automatic callouts of radio height

Findings

- The flight deck crew were properly licensed and medically fit

- The aircraft had been properly maintained and was fit for the flight and the essential aircraft systems were operating normally during the approach.

- The SIERRA approach to Kathmandu is a demanding approach in any wide-bodied aircraft.

- Unlawful interference and extreme weather were not causal factors.

- The crash site was enveloped in cloud at the time of the accident

- There was no ATC clearance error.

- The VORDME beacons used for the approach were operating satisfactorily and there was no evidence of failure or malfunction within the aircraft’s DME equipment

- The aircraft acquired and maintained the correct final approach track but began descent too early and then continued to descend in accordance with an altitude profile which was consistent with being ‘one step ahead’and below the correct profile.

- At 16 DME the co-pilot mis-reported the aircraft’s altitude by 1000 feet.

- The commander did not adhere to the airline’s recommended technique for the final part of the approach which commenced at 10 DME

- The 10 DME position report requested by the Tower controller was made at an altitude below the minimum safe altitude for that portion of the approach.

- The altitude profile on the Jeppesen approach chart which should have been used by the pilots was technically correct. However, the profile illustrated could not be flown in the A300 at V app, in common with any other wide-bodied jet of similar size and the minimum altitude at some DME fixes was not directly associated with the fix.

- The aircraft did not have control column mounted chartboards.

- As described in the report, there is scope for improving the SIERRA approach procedure and its associated charts.

- Kathmandu was not a frequent destination for PIA’S A300 crews and neither pilot had operated that within the previous two months.

- PIA’s training of air crews, briefing material and self-briefing facilities for the SIERRA approach to Kathmandu leave room for improvement.

- PIA’s route checking and flight operations inspection procedures were ineffective.

- The accident was inevitable 15 seconds before impact.

- The Tower controller requested an altitude report immediately after the co-pilot reported at 10 DME. His failure to challenge the low altitude reported at 10 DME was a missed opportunity to prevent the accident but, even if he had done so, it is doubtful whether the accident could have been averted.

- Some air controllers at Kathmandu had a low-self-esteem and was reluctant to intervene in piloting matters such as terrain separation.

- The GPWS was probably serviceable but failed to warn the crew of impending flight towards high ground because of the combination of elderly equipment and rugged terrain.

- Advice within the aircraft manufacturer’s operating manuals regarding pilot reaction to a GPWS warning was incomplete.

- The MEL was being breached in that PIA wen not supplying their CAA with the required carry-forward defect summaries for analysis, neither was the CAA requesting them.

Cause

The balance of evidence suggests that the primary cause of the accident was that one or both pilots consistently failed to follow the approach procedure and inadvertently adopted a profile which, at each DME fix, was one altitude step ahead and below the correct procedure. Why and how that happened could not be determined with certainty because there was no record of the crew’s conversation on the flight deck. Contributory causal factors were thought to be the inevitable complexity of the approach and the associated approach chart.

SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS

- ICAO should review the conventions of commercial approach charts with a view to encouraging standardisation and reducing chart clutter.

- His Majesty’s Government of Nepal, Ministry of Tourism and Civil Aviation, Department of Civil Aviation should re-design the State SIERRA approach chart to comply with ICAO PANS OPS by including a table of recommended minimum altitudes for each nautical mile of the final approach.

- HMG/N, Department of Civil Aviation should improve and simplify the SIERRA approach procedure by addressing the following aspects:

- Unnecessary changes in the glidepath should be eliminated

- The holding pattern should be revised.

- A facility should be provided to validate DME range before the descent below minimum safe en-route altitude commences.

- The chart producers should ensure that their SIERRA approach charts comply with ICAO PANS OPS by including table of recommended minimum altitudes for each nautical mile of the final approach.

- The operator should take steps to stop the dubious practice of some crews transcribing data from approach charts.

- The airline’s crews should be encouraged to alert their management and their pilots’ association to those charts which they consider to be unsatisfactory.

- The airline should fit control column chart clipboards to all its A300s.

- The airline should equip all its aircraft with sufficient lightweight-headsets for each member of the flight crew and those headsets should have boom microphones.

- The airline should adopt the hot microphone system for CVR recordings.

- The airline should expand its briefing material for difficult instrument approaches and make this material available in or very near the crew reporting Centre.

- The airline should practice the SIERRA approach in the simulator as part of the process of pilot qualification to operate to Kathmandu and that such approaches should be part of a line-orientated training session

- The operator should ensure that all its route check pilots are route-checked at least once per year.

- The airline should provide Cockpit Resource Management training as soon as practicable for captains, copilots and flight engineers

- The airline should train its flight engineers to interpret non-precision approach charts and provide them with charts for all non-precision approaches flown by the company.

- The airline should carry out checks of recorded flight data to ensure that company standard operating procedures are being followed.

- The Civil Aviation Authority of Pakistan should appoint and provide flight operations inspectors and the airline should allow them on the flight deck as observers.

- Airlines which operate regular scheduled services to Kathmandu should, where necessary, modify their GPWS equipment to provide automatic callouts of radio height.

- HMG/N Department of Civil Aviation should study the practicalities of providing an instrument landing system (ILS) and radar coverage at Kathmandu.

- HMG/N Department of Civil Aviation should consider taking steps to improve air traffic controller’s motivation, performance and self-esteem by:

- Issuing formal air controller licences.

- Introducing specific controller position training and ratings.

- Introducing periodic competency checks.

- Immediately introducing improved salaries and allowances to operational ATCOs at Tribhuvan International Airport.

- ICAO should sponsor research into improving GPWS technology so as to improve system performance in mountainous terrain.

- Airbus Industrie should amplify the instructions in their Flight Crew Operating Manual regarding pilot response to GPWS warnings.

Captain Iftekhar Janjua was a route check pilot on A300 aircraft. He was not happy to go to Kathmandu. and his reluctance to operate to that airport had been remarked earlier by the Pilots’ Association. He had expressed apprehension of flying to Kathmandu airport and had broken some runway lights while trying to stop the aircraft on an earlier trip on the B707. The Pilot and copilot were not on the best of terms–Mohammad Syed Husain

Update- 27 November 2018: on discussing this accident with my colleagues who were flying for PIA at the time of this mishap and who have flown into Kathmandu, also, before and after the accident, the following information came to light of which I was not aware:

Both the pilot and copilot did their commercial pilot training at the Peshawar Flying Club, hence they had no Air Force flying background. The captain was in the Air Force but not as a pilot for a very brief period of time and leaving the service went into flying as stated above in Peshawar.

The aircraft did not hit the crest of the mountain as reported in the press but much below near the middle portion of the mountain as they tried to duck under the clouds to get a picture of the terrain and break clear of the clouds during the descent for the runway. On sighting the obstacle ahead, full power was applied to clear the mountain in a climb, but it was too late.

The approach plate showing the elevation of the mountain against which AP-BCP collided was incorrect in giving the true altitude by as much as 1000 feet. No small figure. In fact, one of them stated that he flew a one tier lower pattern on the profile descent chart and succeeded in clearing the obstacle where the aircraft had crashed. Both these pilot completed their careers at the highest equipment in the airline, held very responsible assignments in the pilot community and their statement is as authentic and reliable as one from the horse’s mouth,

Their discourse suggested they could not agree (my inference) with the report made out by Amjad Faizi, Chief Of Flight Safety PIA. They held the opinion that ATC wasn’t a factor in the accident. On my probing the cause of accidents generally one of them asserted the lack of instant situational awareness of the aircraft with respect to the physical ground below.

PIA flew the Fokker F-27, B707/720, A300 and the B747 into Kathmandu. I was surprised at taking the Jumbo there but eight charter flights of B747 were operated to that destination in the period after the Kathmandu crash.

AP-BCP after crashing into Fan Marker Hill 9 nautical miles short of runway

Memorials

Good day – I’m a producer with the show ‘Mayday’ which airs on the Discovery Channel. Would be interested in discussing your entry on PIA 268. Would you be able to contact me?

Yes.

Sorry to have missed your call today. I will mark this number so that I do not miss it again if you call. If you are working on Saturday (November 24), please let me know.

I have flown with Captain Iftekhar Janjua (R.M.I. Janjua) to Europe, New York (RF), the Middle East, Hong Kong (RF) and Kano, Nigeria.

On the return sector from Kano, I was sitting on the left seat. We had to delay the flight for over three hours awaiting evening for the milder temperature permitting us to depart. On the takeoff roll, the flight engineer had to take some power off an engine as the exhaust turbine gas indicator was on the red line? I remember, Iftekhar commenting, that the Flight Engineer was a smart guy.

On the way back from Kano, we performed the Umrah (mini Hajj) at Mecca when we night stopped at Jeddah.

In Hong Kong we had to wait a week for the aircraft to come as an intervening flight was cancelled. We met the South African Airlines crew at the hotel crew room where we were lodged. It was the apartheid season at the time. They were flying the 747 SP, Johannesburg to Hong Kong direct, I believe.

In London on way to New York on my RF, we ate lunch at a Pakistani restaurant in Earls Court which was within walking distance from Kensington High Street, where we stayed.

In Damascus, we climbed a mountain to reach the cave where the Biblical and Koranic verses relate the same story of some boys who slept for centuries in a cave. We saw the mausoleum of the first muezzin of Islam, Zayd, and also the grave of one of the Companions of the Prophet, Abu Huraira in the Damascus market. We offered prayers at the Grand Mosque there.

Iftekhar may have felt apprehensive by the presence of clouds covering 7/8 of the sky over Kathmandu in a mountainous environment with maybe thunderstorm activity. Taking the big jet (A300) with its electronic features is different to the B707 with which I operated there. I cannot understand why he didn’t follow the descent profile and committed the error of probably ducking under the clouds, or there was a approach chart reading error.

In one of my flights to Kathmandu from Dacca (Dhaka), I had a captain with me whose status in the cockpit that day was RF. He was senior to me but was sitting on the copilot seat.

Kathmandu was cloudy as we started the approach, the captain(on first officer duty) started engaging in a verbal discussion with the operating first officer about the operation to Kathmandu. At that time, I needed assistance from the copilot to cross check my descent profile with the DME (distance) figures in relation to the altitude. This was no time for such crappy discussion and I felt a moment of apprehension. I was forced to ask the copilot on the observer seat behind me to be alert and talk me down with what I have quoted above. The captain was a dimwit besides a nuisance and he retired as a 747 captain, thanks to the seniority list.

I’m a contributor to Wikipedia. Where did you get the final report? This could help with the article on PIA 268 as it needs more citations.

You can try Transport Safety Board of Canada

I like this site its a master peace ! .

Thanks

This website is a trove of treasure for aviation enthusiasts! Was attracted to search after seeing Mayday making an episode to feature PIA flight 268. Your detail input made me realize how professional and passionate pilots PIA has or had in the past. A big salute to your passion!

Thank you

This Share is awesome and informative.

again factual

In 1992 I was a young man in my

Twenties and I was going into the world of work and got my first job at Heathrow as a security agent 1991 to

1993. I was put on the check in desk

Of PIA and I met the passenger who died on the A300 PIA at Kathmandu these people were on transit from Heathrow to Karachi .

Nice and informative!

It is factual

Thank you for your feedback

It’s onerous to find educated folks on this matter, however you sound like you already know what you’re talking about! Thanks

Do you have any picture of Captain Iftikhar Janjua?

No.

The written text is accurate and verified by my colleagues

Greetings,

First a disclaimer: I am by no means an expert or have any formal education relating to aviation.

My comment is this: I happened to stumble upon a show on TV: “Air Disasters” (season 15 episode 1) which highlights PIA268. I read the official findings and would like to perhaps offer a theory on how the pilots may have got it wrong.

I understand that the pilots got the the landing procedure incorrect. May I propose the following: Both pilots were of Pakistan origin. As I understand, the offical language of Pakistan is Urdu. This language is one of 12 in the world that read Right to Left, not Left to Right. It would not be a stretch to imagine that under the immense stress of such a difficult landing and all that is happening in the cockpit that the pilots out of habit, may have accidently glanced at the procedure and read the flight levels Right to Left which in turn puts them exactly one step ahead of where they should have been, leading to the unfortunate outcome.

I understand what you are trying to convey. In aviation, only English is used in Pakistan to teach and understand. The pilot had to look and read the descent let down in a profile and plan view which he incorrectly did.

I remember a British pilot in dec 1981

When I visited capt abdullah baig

At Heathrow with my father I was going

To pick a letter up from him .. while

Sitting with my father in the opposite

Room I presume capt baig was his

Last day ie retirement and people

We’re signing his farewell card .

The British pilot next door who I

Presume worked for PIA started to

Speck English in a Indian accent in

Other words making fun of Pakistanis

Specking English … in others he Was

Poking fun at capt baig’s English .

As a 14 yr old child you don’t

Understand this until you grow older

And find this very offensive .

Look it’s not the accent of Pakistani

Pilots you need to make fun of but

You need to know if they are able

To communicate and understand and

Look at great aviation legendary

Pilots Pakistan has produced

Likes of capt abdullah baig ,

Shakat h Khan , shahnawaz Khan ,

And the list goes on and on in the

PAF likes of MM Alam , and again

The list goes on and on and on !!!!

The captain has nothing to do with who among the crew goes on the flight, irrespective. It isn’t Nanda Bus Service! The final crew position of all flights going out the next day is posted 24 hours in advance, or at the close of the working day prior, by the scheduling department in the flight operations office where the director flight operations also sits. If somebody reports sick at the last minute, the standby will be picked up. This final crew position list and the standby on the same list is communicated to the Motor Transport Section for pick up two and a half hours before the scheduled departure of the flight.

Regarding the relations between first officer and captain, they were not on speaking terms, which itself is the biggest hazard to flight safety. I have been told of this by my colleagues, much senior to him and myself. Please read the post and your comment has been accepted.

I hope pia airlines takes more safety measures before sending out its flights. The pilots and the staff should be trained to tackle such challenges and prevent causalities. It is nice that all details about such accidents are being shared in news. Even travel portals like Cleartrip should actively share such information about different airlines.

Website : https://www.cleartrip.ae/flight-booking/pakistan-international-airlines.html

The accident happened in 1992